President Ramaphosa and his ministers are hard at work, harnessing the spirit of hope and positivity to unlock opportunities for growth. On the sidelines of the 79th UN General Assembly, the President spoke of the need to raise ambitions beyond the 2% growth rate, declaring that “the things that beset our country are not unknown, they are known”.

At the launch of Phase 2 of Business and Government Partnership, the President double down, this time supported by the Discovery CEO, Adrian Gore, with a growth target of at least 3%. The event focused on reforms in energy, transport and logistics to unlock private sector investments. Though these reforms are necessary, they are likely to yield marginal increments on economic growth that may fall short of the target.

Zooming in on the ‘things that beset our country’, I am of the view that ‘the things’ that beset our country are what I would call ‘the tyranny of the dominant economic narrative’- narrative that wrongly confuses South Africa for a ‘currency user’ dependent on taxes to fund fiscal spending. This is however understandable as most economic textbooks are Western based and written by Westerners with European leanings, perspectives, and experiences.

South Africa is a unique country with its own unique set of challenges and underexplored economic opportunities. Among unique features are its historical journey that gave rise to unique local contexts, including the introduction of a fiat currency, the rand, which transitioned the country from a ‘currency user’ to a ‘currency issuer’ (differences explained below). The rand was introduced by the government, not private sector and this means the rand is not a crypto currency. The transition between the two states ought to have been accompanied by changes in approaches to fiscal policies but didn’t and sadly, hasn’t changed.

Before explaining the reasons why South Africa is held back by the ‘tyranny of the dominant economic narrative’, let me explain four things: difference between currency users versus currency issuers, two types of rands, monetary sovereignty and international hierarchy of currencies. All these give the government immense leverage on fiscal policies that remains underexplored, resulting in persisting triple social challenges of high unemployment, poverty and inequality.

Be forewarned, this is a long article, for South Africa’s triple social challenges are long in the making, intractable and complex.

Currency user versus currency issuer

Currency users are countries that do not have legal constitutional ability to issue their own currencies. Examples of currency users are all countries in the eurozone as the euro is issued by the supranational European Central Bank. Currency users are dependent on taxes to fund fiscal spending. Currency issuers, on the other hand, have constitutional, legal and institutional abilities to issue their own currencies. Examples of currency issuers are South Africa, Botswana, Eswatini, Britain, United States and China and others. While taxes are important for currency users, they perform entirely different functions and are not the source of funds to finance fiscal spending.

Public rand versus private rand

South Africa has two kinds of rands in circulation, depending on the source of creation: 1) public rand issued by the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) and 2) private rand issued commercial banks. These two types of rands are identical in all respects, trading at par and fungible (indistinguishable once in circulation). Public rand is issued and enters circulation through fiscal spending while private rand is created through approved loans deposited into accounts of individuals and corporates. Access to private rands is dependent upon several factors, including credit quality of debtors, state of the economy, level of interest rates and resource endowments. There is no equal opportunity to access newly created private rands. All else, salaries, wages, business incomes, are derived from the already created money in circulation. Unlike the private rand, public rand has egalitarian properties as its issuance/creation is not dependent on prior resource endowment.

International hierarchy of currencies

Global currencies are ranked according to their ability to function as money—unit of account, medium of exchange, and store of value—at an international level as well as an international reserve currency. At the top of the hierarchy are the top currencies such as the US dollar, euro and the pound sterling[i]. At the bottom are currencies issued by developing and poor economies, called ‘peripheral’ currencies, including the rand.

These peripheral currencies do not perform classical functions of money at an international level and are only internationally demanded as financial assets in search of yields. Countries with top currencies have higher freedom on fiscal policies than peripheral countries who are exposed to frequent bouts of ‘flight to safety’ of the top currencies during periods of heightened geopolitical risks and other exogenous global shocks[ii].

The rand has a good standing in the region. It was once part of the Rand Monetary Area (RMA) established in 1974 through which the rand was a legal tender in Botswana, Namibia and Swaziland (Eswatini). In 1986, RMA was replaced with Common Monetary Area (CMA) to align monetary policies. Therefore, the rand does function as money at a regional level, giving South Africa regional privileges in the government procurement of physical resources.

Monetary sovereignty

Monetary sovereignty is the power of a state to exercise exclusive legal control over its currency, its issuance, and retirement. This includes ability of a state to maintain independent exchange rate. In essence, monetary sovereignty is freedom in formulating and implementing fiscal and monetary policies and exists on a continuum, from high form of monetary sovereignty to a weak form. A country able to issue its own currency that can function as money at international level and has a flexible exchange rate starts off with high form of monetary sovereignty. Such level of sovereignty is lost each time a country enters foreign denominated debt contracts[iii]. In public finance, entering government debt contracts in foreign currency is often considered an ‘original sin’[iv].

Countries with higher proportion of government debt in foreign currencies, being currency users and those maintaining currency pegs have low form of monetary sovereignty. Countries such as the US, Canada, and Japan have debt-to-gdp ratios of more than 100% with all of it in their own respective currencies, giving them high policy freedom and flexibility. At the other extreme are countries whose sovereign debts are wholly denominated in foreign currencies and thus having a very weak form of monetary sovereignty. Still, many countries, including South Africa, are in the middle of the continuum.

The location of the rand on the international hierarchy of currencies and low government debt denominated in foreign currencies give South Africa high freedom on fiscal and monetary policies.

Unrelenting fiscal consolidation

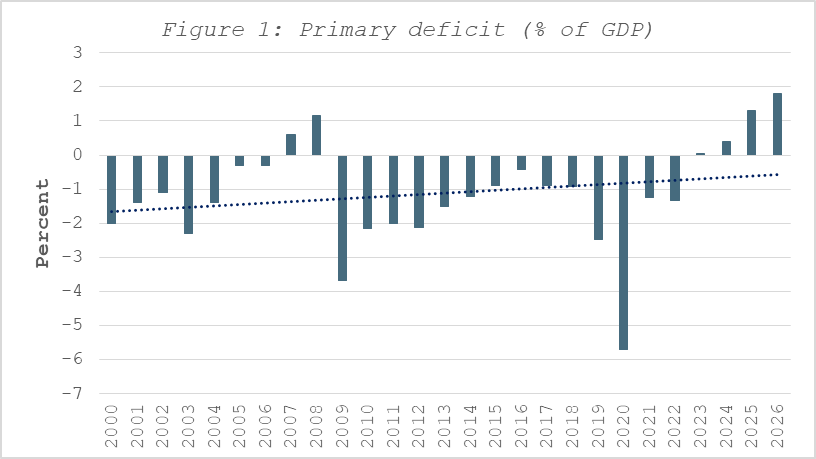

Democratic government has been on an unrelenting path of fiscal consolidation with periods of temporary breaks to respond to exogenous shocks such as the 2009 global financial crisis (GFC) and COVID19. These two periods forced the government to implement countercyclical fiscal measures, which proved effective in reigniting economic growth- a clue to solving the current ‘secular stagnation’ – era of near zero-growth rates.

The tenure of Trevor Manuel was dominated by the desire to achieve fiscal surpluses, eventually achieved in 2007 and 2008 on the back of high commodity prices. Tax receipts were greater than fiscal spending, leading to fiscal surpluses. Unfortunately for a fiat currency issuer like South Africa, tax payments amount to withdrawal of money from circulation, starving the country of the much-needed liquidity. As budget outlook shows in figure 1, Minister Godongwana is steadfast on the tradition set by his predecessors.

Source: Soutth African Reserve Bank

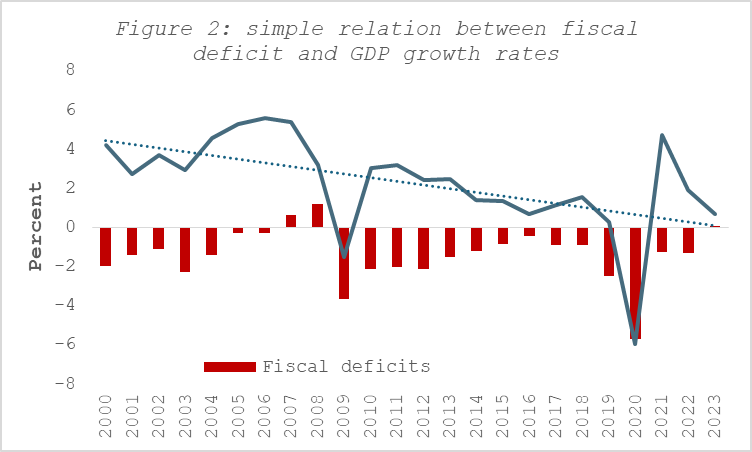

Overlaying economic growth with fiscal deficits bring out unmistakable simple positive correlation between growth rates and fiscal deficits (see figure 2). It is an undisputable fact that post fiscal surpluses, there has been a step down in economic growth rates. Like South Africa’s low growth era, post 2008, America also entered low growth period post the Clinton’s fiscal surpluses of 1998 to 2001. Some economists are of the view that it is the Clinton’s fiscal surplus that triggered the Asian Financial Crisis by draining too much US-dollars from the global financial system.

Growth rates have not only been sliding downwards since 2007 along with intensifying budget sequestration but have now entered the phase of secular stagnation.

Source: Soutth African Reserve Bank

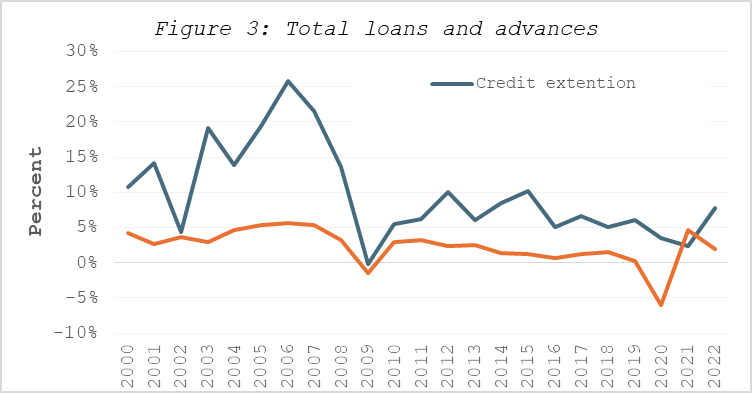

Credit extension to private sector

With the government steeped on austerity, the economy is left with commercial banks as creators of new fresh liquidity through bank loans. Credit extension to the private sector wax and wane over time influenced by number of factors, including changes in interest rate and the prevailing economic conditions. Prior to the GFC, private credit extension was increasing at average rate of 16% per year (3,5 times that of GDP) (see figure 3). Post GFC, loans and advances grew at a much slower pace, averaging 6% per year. With taxes and loan repayments withdrawing money from circulation, new money creation is critical to keep economic activities running. For the most part, growth in loans and advances exceeded economic growth without endangering inflation.

Source: SA Reserve Bank

With finance now accounting for 24% of the GDP (up from 16% in 2000) relative to 8% of the government, economy is highly financialized. A financialized economy is a rentier economy, strongly associated with rentier interests and income extraction, both from non-financial firms and workers. Unemployment tends to higher in financialized economies as rent seeking activities detract from real economic activities.

Conclusion

South Africa has huge economic potential that however remains unrealised due to the ‘tyranny of the dominant economic narrative’. The country has its own currency -a regional hegemon, maintains flexible exchange rate and much of the government debt is in rands. All these factors means that the government has high freedom and flexibility (high form of monetary sovereignty) on fiscal and monetary policies. The key to unlocking growth is not with private sector but with government and at fiscal policy level. Government should go back to the basics and recognize the centrality of its role in the economy. Reforms, though necessary, will only bring about marginal increments on economic growth. Opportunities for higher growth will be unlocked through properly calibrated and targeted increase in fiscal spending in key areas of deficiencies (education, health, energy, infrastructure and others). To be clear, this is not an argument for wanton increase in fiscal deficit that can stoke inflation but a more intentional and targeted increase in identified bottlenecks areas.

Endnotes

[i] Cohen, B. J. (2000). The Geography of Money. Cornell University Press. https://doi.org/doi:10.7591/9781501722592

[ii] Patrício Ferreira Lima, K. (2022). Sovereign Solvency as Monetary Power. Journal of International Economic Law, 25(3), 424–446. https://doi.org/10.1093/jiel/jgac029

[iii] Ibid

[iv] Eichengreen, B., Hausmann, R., & Panizza, U. (2002). Original sin: The pain, the mystery, and the road to redemption.